Nothing in the Gutter

An Aphantasic Critique of McCloud’s Understanding Comics17 Feb 2024

This is an essay I wrote in university for ENG235H5: Comics and the Graphic Novel. I am quite proud of this essay, and thus decided to post it here. It was originally written on April 6th, 2023.

Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics is a deeply influential book in comic analysis, and has influenced the creation of most, if not all, comics made after its release. In it, McCloud discusses many ideas about the reading of comics, and in doing so, makes several assumptions about the readers of comics. While many of his assumptions are reasonable, there is a group of readers of his work that may feel left behind: readers with aphantasia.

Aphantasia is a condition defined by a lack of ability to form mental imagery. For those with this condition, dubbed “aphants,” the idea of counting sheep to fall asleep is a fanciful metaphor. When asked to imagine something, they still conceptualize the object, and are very capable of imagining through this lens, but they have no “mind’s eye” to see anything. While the term aphantasia is limited to imagery and the sense of sight, aphants are more likely than other members of the population to have a similar inability to access other senses within their mind as well. There is a wide variety in people’s experiences with aphantasia, with some claiming to be able to visualize words or numbers, whereas others perceive nothing more than an empty void.

The third chapter of Understanding Comics, “Blood in the Gutter,” is focused on the idea of closure, and particularly how it relates to transitions between panels in comics. McCloud defines closure as the “phenomenon of observing the parts but perceiving the whole” (63). McCloud uses the idea of closure to justify the reader’s ability to comprehend that which happens between the panels. He also considers the merging of panels into a single idea through closure an active act on the part of the reader, where they, as an “accomplice” to author, will construct a version of the scene within their minds to fill in those literal gaps.

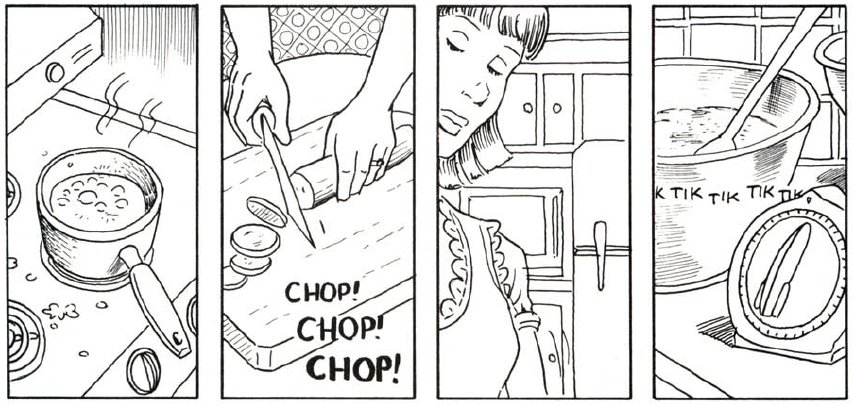

For a reader with aphantasia, this concept may not match with their experience of reading a comic. An aphant will still conceptualize the intermediate steps between panels, coming to conclusions logically, and potentially injecting their own narrative understanding. The distinction between this understanding and McCloud’s understanding of a reader’s closure is apparent near the end of Blood in the Gutter, where he presents a scene of a kitchen, shown in Figure 1. He then proceeds to ask the reader some questions:

Fig. 1. A sequence of 4 panels, showing a kitchen. In the first panel, a pot boils on the stove. In the second panel, a cucumber is sliced on a cutting board, with the sound effects “Chop! Chop! Chop!” appearing sequentially in increasing size. In the third panel, a woman is looking down at her cutting, with the background showing the fridge and cabinets. In the fourth panel, an egg timer sits next to a bowl filled with a mixture, and the sound effect “Tik” is repeated multiple times above the timer. (McCloud, 88)

Fig. 1. A sequence of 4 panels, showing a kitchen. In the first panel, a pot boils on the stove. In the second panel, a cucumber is sliced on a cutting board, with the sound effects “Chop! Chop! Chop!” appearing sequentially in increasing size. In the third panel, a woman is looking down at her cutting, with the background showing the fridge and cabinets. In the fourth panel, an egg timer sits next to a bowl filled with a mixture, and the sound effect “Tik” is repeated multiple times above the timer. (McCloud, 88)

Now, most of you should have no trouble perceiving that you’re in a kitchen from those four panels alone. With a high degree of closure, your mind is taking four picture fragments and constructing an entire scene out of those fragments. But the scene your mind constructs from those four panels is a very different place from the scene constructed from our traditional one-panel establishing shot!

Look again.

You’ve been in kitchens before, you know what a pot on the boil sounds like; do you only hear it in that first panel? And what about the chopping sound? Does that last only a panel or does it persist? Can you smell this kitchen? Feel it? Taste it? (89)

These questions posed only make sense to a non-aphant reader. To a reader lacking internal senses with which to hear and smell and feel and taste, the questions seem ridiculous, and to aphant readers who are unaware that their existence is not the norm, the process of discovering through these sorts of questions that other people can perceive these things in their minds can be quite alienating and confusing.

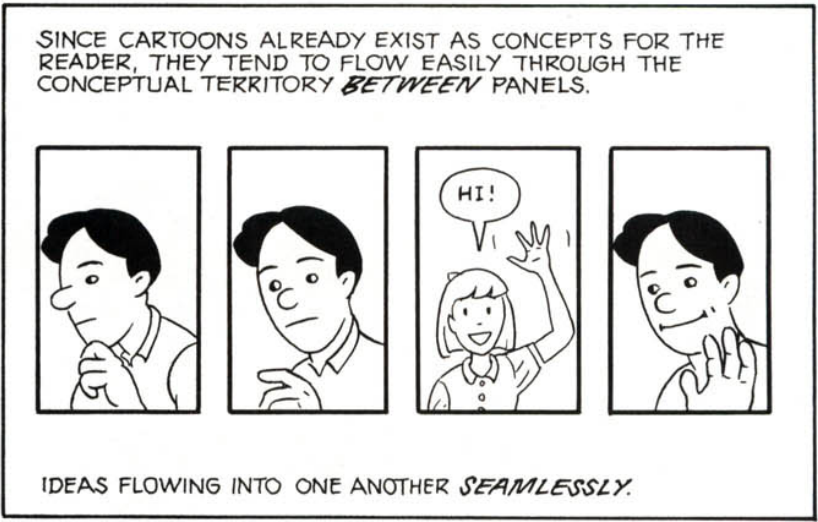

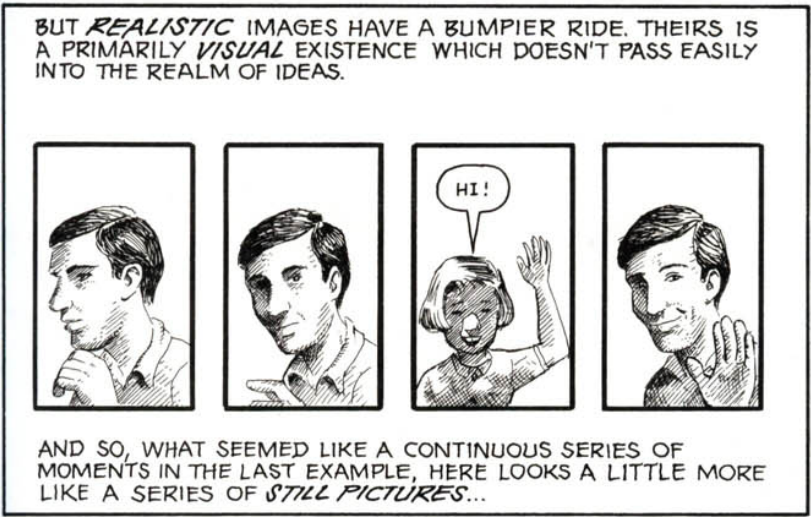

McCloud’s ideas on closure and their connection to iconic and non-iconic imagery can also feel distinct from an aphant perspective. McCloud argues in Figures 2 and 3 that more realistic art styles lend themselves to being perceived as “a series of still pictures” (91) rather than a single idea, in his subjective experience. To an aphant reader, both sequences are nothing more than a series of still pictures, neither one truly lending themselves to more or less ability to visualize what happens between the panels.

Fig. 2. A series of 4 panels of a man in thought being waved to by a young girl. In a relatively cartoonish style, juxtaposed to Fig. 3. Text surrounds the panels, reading “Since cartoons already exist as concepts for the reader, they tend to flow easily through conceptual territory between panels. Ideas flowing into one another seamlessly.” (McCloud, 90)

Fig. 2. A series of 4 panels of a man in thought being waved to by a young girl. In a relatively cartoonish style, juxtaposed to Fig. 3. Text surrounds the panels, reading “Since cartoons already exist as concepts for the reader, they tend to flow easily through conceptual territory between panels. Ideas flowing into one another seamlessly.” (McCloud, 90)

Fig. 3. A series of 4 panels of a man in thought being waved to by a young girl. In a relatively realistic style, juxtaposed to Fig. 2. Text surrounds the panels, reading “But realistic images have a bumpier ride. Theirs is a primarily visual existence which doesn’t easily pass into the realm of ideas. And so, what seemed like a continuous series of movements in the last example here looks a little more like a series of still pictures…” (McCloud, 91)

Fig. 3. A series of 4 panels of a man in thought being waved to by a young girl. In a relatively realistic style, juxtaposed to Fig. 2. Text surrounds the panels, reading “But realistic images have a bumpier ride. Theirs is a primarily visual existence which doesn’t easily pass into the realm of ideas. And so, what seemed like a continuous series of movements in the last example here looks a little more like a series of still pictures…” (McCloud, 91)

The lack of ability for an aphant to visualize within their mind’s eye means that the only visual of the world of the comic is that which they can see. This visual literalism lends itself to readings of distinctive art styles as not merely stylized representations of reality, but accurate representations of stylized realities. That is to say, the world inside of the comic itself is a cartoon world, that relies on cartoon rules. Depending on the work, this type of reading may be more accurate than not. For example, One Piece by Eiichiro Oda is a famously stylized manga series. However, the distinctive art is also true and literal within the world of One Piece. Large, distinctive facial features such as Usopp’s long nose are literally perceived as such, and on more than one occasion he is mistaken for another character with a similarly long nose (chapter 326, pages 4-6). Another example is the way in which the main character Luffy can increase the power of his attacks by inflating his own limbs, which under normal circumstances would make those limbs simply full of air, increasing their volume without affecting their mass; however within the cartoon world, it makes them bigger, and thus heavier, and thus they hit harder.

This idea of visual literalism is in distinct conflict with McCloud’s ideas of the purpose of the cartoon. To McCloud, cartoons are effective as vessels to be projected onto because cartoons are the way in which people are aware of their own sense of self, internally (36). Once again this falls apart for aphants, because an aphant can’t perceive themselves visually without the aid of a mirror. They must simply conceptualize themselves and their appearance through more verbal descriptors. “The left side of my mouth is raised slightly in a smirk,” might be a thought running through an aphant’s head, but they can’t see it as a cartoon any more than they could see a realistic version of their face. Without that internal self-perception, a cartoon is no more effective a vessel for self-projection than a realistic image is.

Many of McCloud’s ideas regarding closure and the cartoon are reliant on internal perceptions of all kinds, but most of all on internal visualizations. Such ideas fail to take hold on an aphant mind, beyond being a fascinating glimpse into the non-aphant way of seeing the world. Aphantasia is a condition that was only coined in 2015, and with such a recent understanding of some people’s mentalities comes the exciting prospect of study into the ways various types of art can affect those who think differently. As McCloud says: “We all live in a state of profound isolation. No other human being can ever know what it’s like to be you from the inside” (194). While communication and art exist to try to communicate those ideas from one person to another, sometimes the most interesting communications can be had when someone tries to communicate not just what they are thinking, but how they are thinking it.

Works Cited

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. HarperCollins, 1994.

Oda, Eiichiro. One Piece. Shueisha, 1997-Present.